The Bodyguard Turned Bicyclist

For Ah Biao, his mobility is the symbol of his independence.

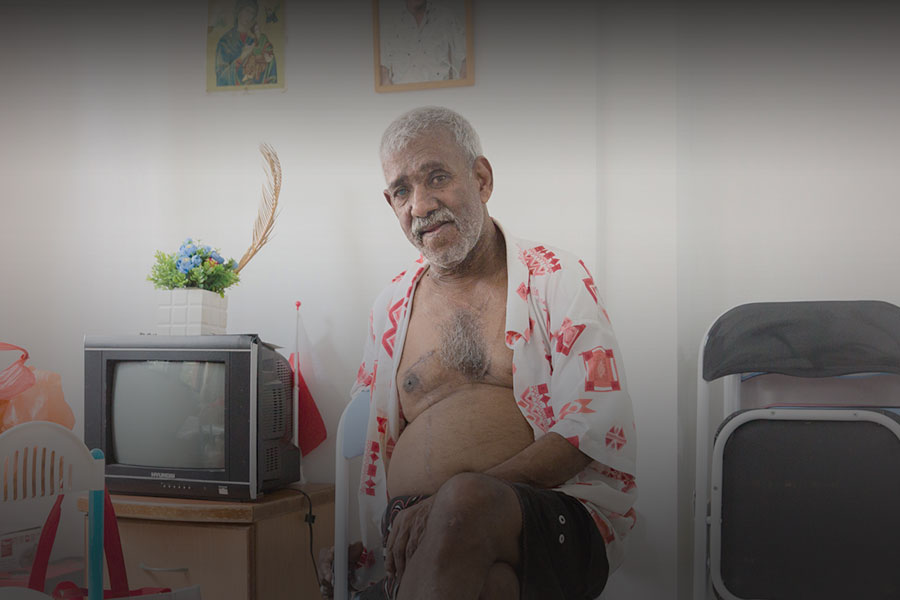

Take a walk around Dakota Crescent, you might likely catch a glimpse of Mr Lam Tem Peau, one of the regular elderly cyclists in the estate. Known as Ah Biao to his familiars, he spends most of his hours on his bicycle and is hardly seen without it.

On the rare occasion that we manage to catch Ah Biao at home, he welcomes us into his sparsely-furnished flat, one of the ground floor units at Block 6. While the flat is two-room in name, Ah Biao lives out of his living room, leaving the bedroom untouched.

The house is arranged in an easily accessible manner, a careful consideration he has made due to his old age. His laundry line is next to his bed; the kitchen a few steps away, then the toilet. On the wall, a small portrait of Buddha next to a card made by students from Kong Hwa Secondary.

Explore Ah Biao’s house in 360

My dad modified my age on my cardboard IC when the British were looking for locals to fight in World War 2.

Ah Biao

His Singapore Story

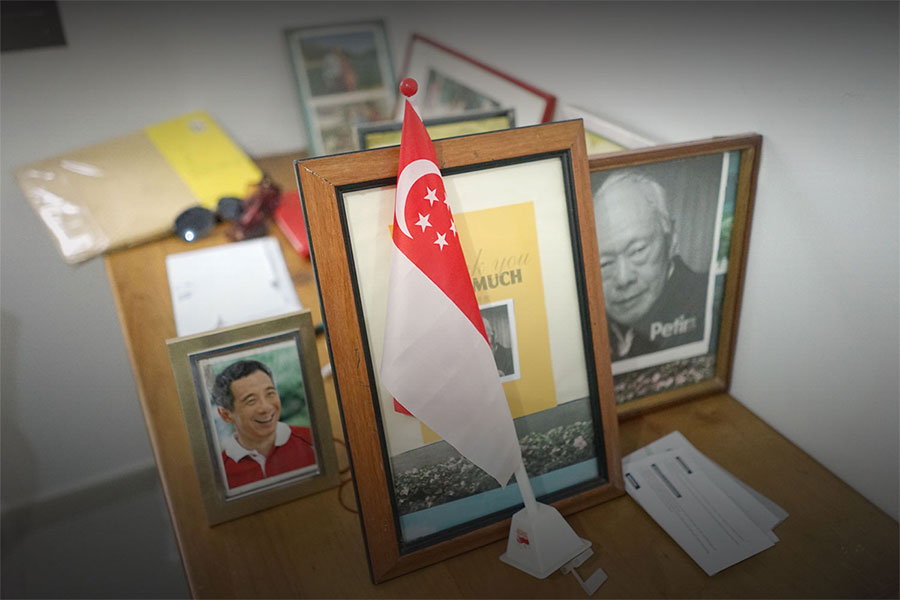

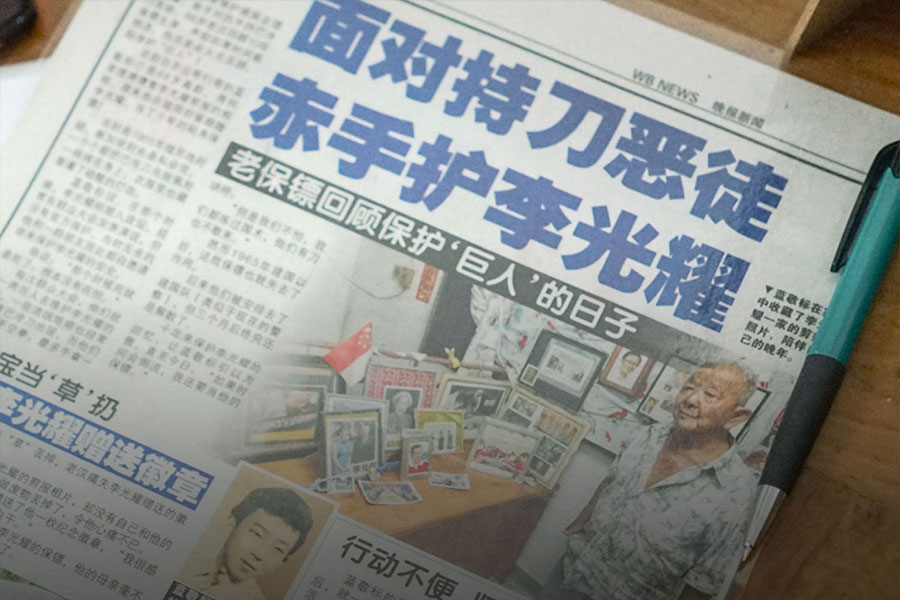

Ah Biao shot into the limelight a few years ago, when Shin Min Daily published a story about his life and his stint working as the bodyguard for Lee Kuan Yew in the 1960s, who was then the Prime Minister.

He remembers guarding Lee Kuan Yew for a period of time before he came to power. And he does not place much emphasis on it – “It was just a bunch of friends, helping him out,” he says.

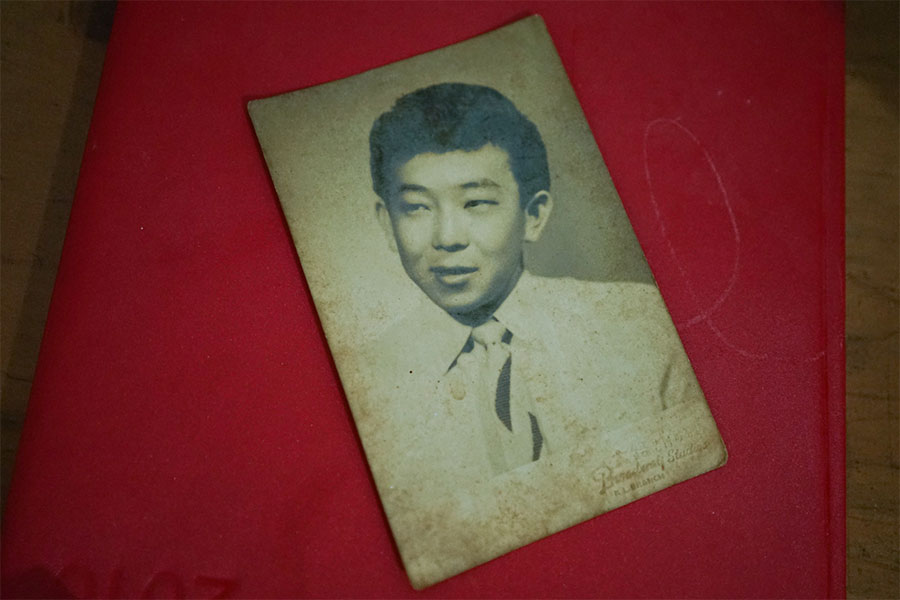

Ah Biao’s bronzed, weather-worn face speaks of a lifetime of experience, and seems even older than the 78 years of age printed on his identity card. In fact, he is almost 90. “My dad modified my age on my cardboard IC when the British were looking for locals to fight in World War 2,” he says.

Start any conversation with Ah Biao, and the topic would always veer to include Singapore’s late founding Prime Minister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew. He credits Lee Kuan Yew for bringing Singapore to her current developmental level, often saying, “If there wasn’t Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore would not be what it is.”

Singapore’s independence meant a lot to Ah Biao, and not just because of his patriotic sentiments. In his younger years, he had worked in the construction sector, which had developed strongly under the Government’s push to modernise Singapore.

“I know how to read architectural blueprints,” he says. “But who would want to hire an old man like me now?” he muses. While he was fairly successful in construction, he subsequently lost most of his savings on some bad bets on horses. “My ears are no good, they heard that I could make millions at the horses,” he lamented.

The Cycle of Debts

Ah Biao first moved to Dakota Crescent some forty years ago and has been on public assistance since he retired. Under the Ministry of Social And Family Development’s ComCare Long Term Assistance Plan, he receives a monthly S$500 payout for his daily living expenses.

However, Ah Biao reveals that this sum of money is insufficient for his day-to-day needs. More often than not, the money runs out in two weeks. Between then and the next payout, Ah Biao has to establish credit terms with hawkers at the wet market opposite Dakota Crescent and taxi drivers he knows.

“I am not a bad person,” he says. “I repay all of them once I receive the money.”

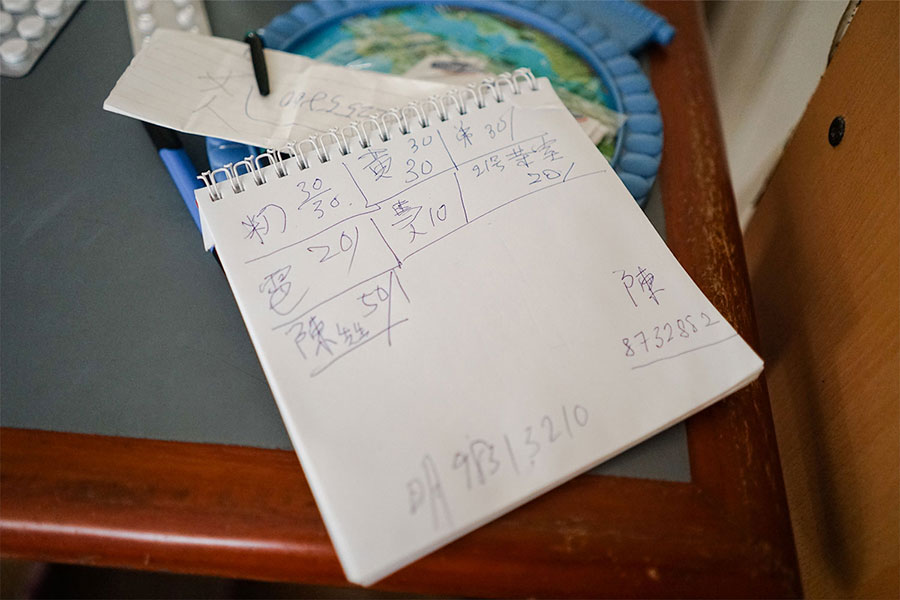

He takes out a notebook. In it is his ledger, a list of people whom he owes money to. On it, a list of around 5-7 people which he owes between $10 – $30.

He confesses that money is the biggest issue in his life now, more so than the move. He does not say it explicitly, but throughout our conversations with him – it is clear that he hopes that the moving allowance of $1,000 would help him break out of the borrowing cycle. “When the money comes in, maybe it will become better,” says Ah Biao.

Getting the money was not an easy task. In order to receive the full sum from HDB, tenants would have to ensure that their flats are properly vacated. This was a tall order for someone as elderly as Ah Biao. In the weeks leading to his move from Dakota, he made many slow and arduous journeys to the nearby rubbish dump to get rid of the items he would not be bringing to his new one-room flat.

“In a couple of years, if I can’t walk, I will commit suicide. At least I will not trouble others any further.”

Towards the Future

Nostalgia is not high on Ah Biao’s list of moving considerations, unlike some residents of Dakota. Here, a little pride of his years spent in construction shines through.

“The foundations of these old buildings are made from wood, not cement or stone,” he says. “They are like tofu – and given their age, I think it is a good thing the government is tearing these flats down. It might not be safe after all these years.”

While he looks forward to the move, and the allowance that comes with it, Ah Biao still has reservations about the future and what it may bring for him. He has had high blood pressure for the last thirty years and is on subsidised medication to keep it controlled. “At my age” he says, “I can only take each day as it comes”.

At my age, I can only take each day as it comes.

Ah Biao

Ah Biao is aware of his dependence on the people around him, and more often than not, he seems rather embarrassed that he is reliant on the kindness of others to get by day to day. “In a couple of years, if I can’t walk, I will commit suicide.” Ah Biao says in all seriousness. “At least I will not trouble others any further.”

After our conversation, Ah Biao leaves to go out for lunch, despite our offers to buy him a meal. He ambles over to his bicycle, which he parks at the rear of his ground-floor flat.

As we watch him cycle slowly away, the air of mystery around his life dissipates, and what remains apparent is the strength of a man who simply wants to stand on his own two feet, for as long as it is possible.

Researched & Written by Wan Zhong Hao

Photography / videography by Charmaine Poh, Wan Zhonghao, Cheah Wenqi