A New Chapter On Her Own

A woman whose move helped her grieve.

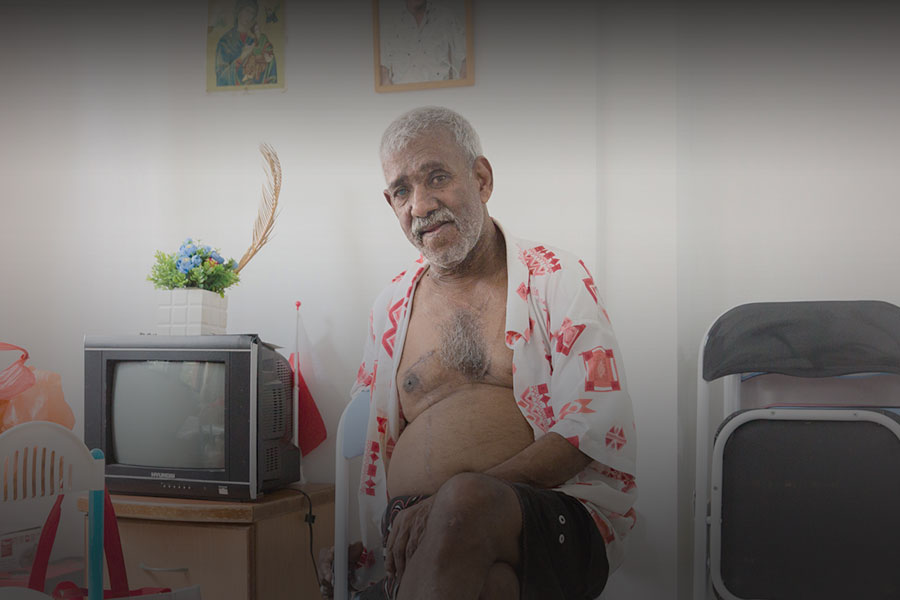

It is one of our first few visits to Mdm Tay Soi Yeng, 56, at her ground-floor apartment unit. She sits in the living room, on a wooden low-rise chair, watching television. The afternoon light streams in, casting her in a soft glow.

Her wheelchair remains nearby. Having suffered a stroke a couple of years ago, and with the added pain of arthritis, Mdm Tay has limited mobility and remains seated much of the time.

When I heard the news, my husband was still here.

Mdm Tay

An Emotional Reminder of Her Husband

Mdm Tay is a widow, who lives with her niece, Lie Shuen, at Dakota Crescent.

She is slated to move nearby to Block 52 Cassia Crescent, a new block set aside for the rental flat residents of Dakota Crescent.

“When I heard the news, my husband was still here,” she said. “Little did I know that my husband would pass away.”

Unlike some other residents, who complain about the logistical difficulties or the loss of community and space, for her, every step of the move is more of an emotional reminder of the husband she used to rely on. Being a housewife all her life, she is used to depending on her husband for all administrative matters.

“I’m slowly learning. In the past, I didn’t know anything, I let him take care of everything. Like those house matters. Things I need to sign, I won’t worry about it. I’m just responsible to sign, and that’s it.”

The matters of the move have proven more confusing when the official letters sent by the HDB are only in English, which she is unable to read.

“I give my niece Lie Shuen [the letters] to read. Give them to read for a bit, also give to Shawn (her nephew) to read a bit. See how it’s like. After it’s read and if I’m still not sure, I will give it to the people at the daycare to read. They will help me explain what to do.”

This will also be the first time she’s living alone. Because her niece is not part of her immediate family, she can only apply for an apartment with one living area, and no separate bedroom or kitchen.

Her niece, who takes care of Mdm Tay after her husband passed away, now has to rent a room of her own, separate from her.

“She might live with me, but even then, we cannot get a bigger house because the flat is registered under my name. If I want to stay, I will be staying alone. My niece can live with me, but there still wouldn’t be rooms.”

Her husband’s death during the moving process meant a change of expectations to the type of apartment she could apply for.

“We discussed and said that if we move, we’d like to stay in a flat with a few rooms, we thought we’d like one room and one living room, and it’s better that way,” she recounts.

“The government didn’t want to give one room and one living room, but give me a place with no room. There was no choice. So I accepted it.”

Because my husband told my church friends that one day, when I’m no longer here, my wife will need you. Please help her.

Mdm Tay

Building a Home in Dakota Crescent

“In all our 37 years of marriage, we’ve only quarrelled once.” she says of her husband, who passed away a year ago from cancer. Tears well up in her eyes, and she slowly wipes them away. It is a scene that becomes familiar as we spend time in the household; Mdm Tay sitting, and once in a while, grieving.

She says he appears to her in dreams. “I saw Jesus bring him back. Jesus talked to me, then called my husband to talk to me. He wanted me to be well.”

“There was another time, he came to see me, asked me why I didn’t listen to him, that I need to live well. Because that period I was constantly heartbroken, and in the dream he scolded me. So I know he is for me.”

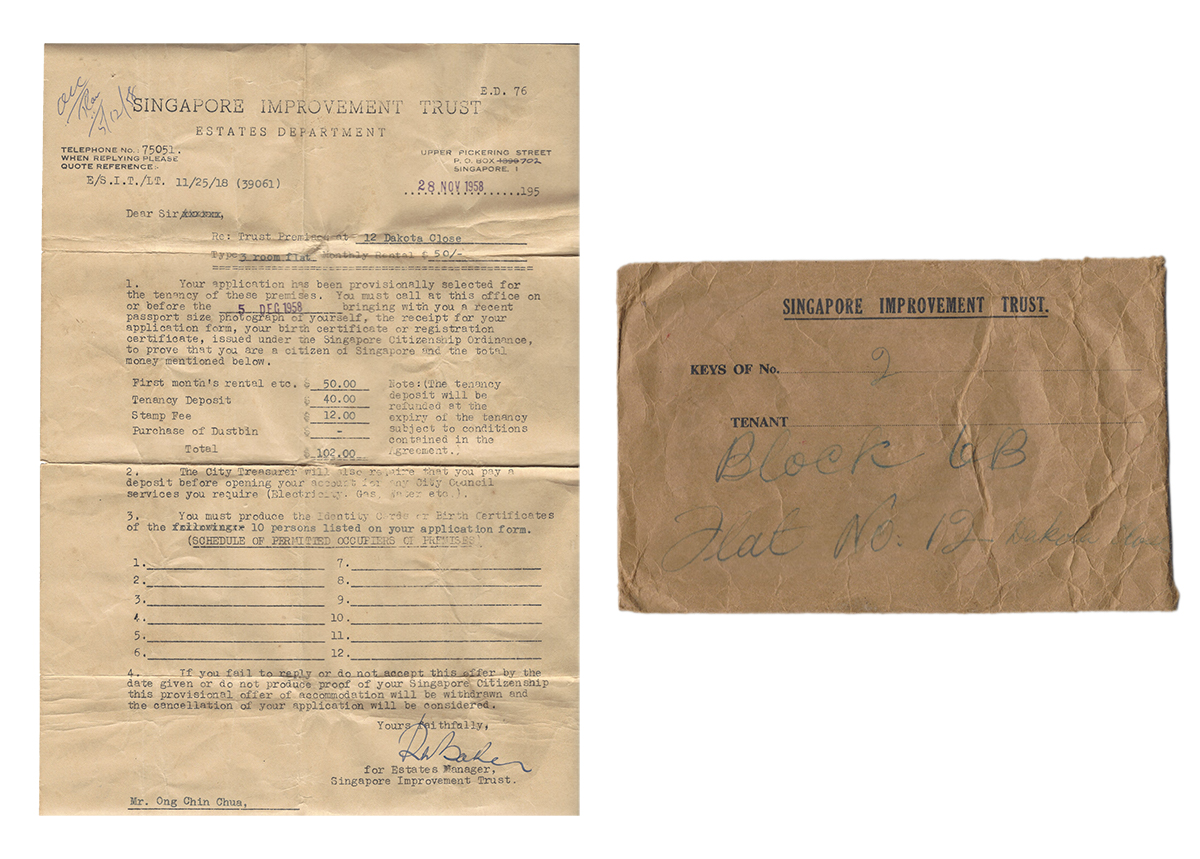

SIT Tenancy Letter and Keys Envelope

Mdm Tay and her husband moved into their marital home at Dakota Crescent 37 years ago. It is the place of her entire adulthood, of the life she and her husband had carved out for themselves.

“Last time when I was healthy, I’d cook. Take care of children, other people’s children. Before I had the stroke, household chores. But then I couldn’t, I was too sad. But now it’s better. My friends said, you need to courageously go on. Slowly, I will be able to.”

Explore Mdm Tay’s home in 360

She bursts into tears occasionally, whenever she is reminded in the slightest of her husband. Among the pictures displayed in her home are photographs of them, smiling, at times with his arm wrapped around her. With the move, she will be letting go not just of a physical space, but of the home they had built together. It is unsurprising, then, that she has mixed feelings.

“There’s both happiness and sadness. Going to a new place will always bring happiness. But I’ve lived here for so long. Such freedom. Moving and changing will always make me afraid.”

According to her memory, Dakota Crescent itself has changed.

“Neighbours. Left and right, neighbours will help. In the past it used to be very lively. Now it’s quite desolate,” she explains. “Children grown up and move out for their own families. And it changed to all elderly.”

Mdm Tay looks away.

What are you thinking about, we ask.

“Nothing. Sian. Must move also no choice.”

Must move also no choice.

Mdm Tay

Finding Her Community

For all of her vulnerabilities, Mdm Tay has found a community after her husband’s death, people have subsequently rallied around her throughout the entire relocation process.

“In the past, I didn’t believe in God. I worshipped deities. Then, my husband kept telling me, you believe in God. They (the church) will take care of you, help you. I thought, since he wants me to believe in God, I will go and see how it’s like. When I went, the feeling was very good. Everyone was very helpful. So I went. Their people are really good. Even my own brothers and sisters aren’t as good.

Her weekdays are spent at House of Joy Centre, a nearby church-run daycare at Pine Close, where there are activities including light exercise, craftwork, and karaoke sessions. And every Sunday, the church community picks her up from her home and ferries her to morning church services. She and her husband started attending church together a few years ago.

“Because my husband told my church friends that one day, when I’m no longer here, my wife will need you. Please help her. She doesn’t know much. The daycare people said, okay. So I’m very grateful for them. Whatever it is, my husband has prepared for it well.”

Since being restricted to a wheelchair, her interaction with the neighbourhood community is now limited to supplies delivered to her by Roger and the Tung Ling Community Services centre he runs. They bring her food and other necessities under the ComCare scheme, a social assistance programme for low-income households.

“They care deeply for the elderly. Whenever we need help to buy things, they will buy it for us and place it at our doorsteps,” she says, describing Roger and his colleagues at Tung Ling.

“For example today, even though I told them that there were people coming to interview me so there is no need to buy food for me, they still bought the food and delivered it at around 9 am. They called to inform me that the food is outside and reminded me to eat it.”

They are quite good, but I don’t want to communicate with them too often. I don’t know. Maybe because I feel ashamed. And I’m alone. I feel ashamed.

Mdm Tay

There Is Nothing To Say

During a visit to the new apartment, she wheels around, inspecting her new abode. It will be a place of new beginnings, furnished with mostly new items.

“It’s too small. But for one person it should be enough.”

During this phase of the impending move, the church community as well as her niece and nephew have rallied around her. Some are present as she attends her appointments with the Housing Development Board (HDB), as well as when she packs her items and gets ready to move.

“Whatever I want to do, I’ll tell him,” she said, referring to Shawn, her nephew. “He’ll come up with the solution. Like tomorrow he’s going to help me with the tap in the toilet, and to buy a new fridge. He can’t make it tomorrow so the day after. I’ll see how, I’ll call my friend. If tomorrow is possible then it’s good. Or I’ll ask my brother.”

Her gratitude, however, is mixed with a slight unease at the knowledge that she requires so much assistance.

“They are quite good, but I don’t want to communicate with them too often,” she continues, “I don’t know. Maybe because I feel ashamed. And I’m alone. I feel ashamed.”

In the process of moving, she throws out many of her husband’s belongings. During one Saturday afternoon visit, her church friends are busy emptying out a room, as she sits on her bed and begins to cry as she decides which of his items to keep. Lie Shuen sits down to comfort her and offers her a piece of tissue.

“There’s excitement, but I also can’t bear to leave it. I can’t bear to leave because I’ve lived here for so long, excited because I don’t know what the new place will be like.”

Mdm Tay approaches the move with the resignation of a person who has come to terms with forgoing autonomy. When asked about her opinions on having to relocate, she shrugs.

“It doesn’t really matter if I’m satisfied or not, it doesn’t change anything. But generally it is okay.” Later, she says, “I can’t bear to leave, but what choice is there since the government told us to move?”

It is a common refrain among citizens unused to dialogue with policymakers. “How can I not follow along with government decisions? Whatever the government says, I will follow suit,” Mdm Tay says. When suggested that a dialogue with policymakers was possible, she replies,

“Who are we? They are the government. What can we say to them? There is nothing to say.”

It’s memories of him. Although I have thrown his things away, he still lives in my memory and inside my heart.

Mdm Tay

A New Chapter In Cassia Crescent

A few months after her move, we make another visit to her apartment. She seems content with her move; it appears to be not as bad as she had imagined.

“My nephew and niece often visit me, once a week or every two weeks. When Lie Shuen (her niece) comes to visit, she’ll stay at my place for one, two days.”

Not much has changed, except that her apartment has fewer of her husband’s items. In the downsizing of the apartment, she has inadvertently created a new space for herself, filled with new memories. The walls aren’t filled with pictures. The rooms don’t hold memories of them together. She says she doesn’t cry as much anymore.

“It’s memories of him. Although I have thrown his things away, he still lives in my memory and inside my heart.”

“Right now, I don’t think of him, I just remember that he has really gone up to heaven. I want to follow him there so I try to do good so that I can follow him to heaven.”

As the block’s community centre, Thye Hua Kwan, focuses on residents that are above 60 years old, 57-year-old Mdm Tay relies on herself on weekends and continues to go to the daycare on weekdays.

“They said that I’m not qualified to go. I need to be 60 years old and above to join,” and adds that she has now turned to her siblings, helping their relationships to improve.

“I don’t want people to help me for anything. However, my friend used to tell me that regardless of the situation, they are still your siblings. How can you handle if you never ask them to help you?”

“I conceded. Subsequently, I started to call my siblings and talk to them. Even when I am not asking them for help, it’s good to ask how they are doing. So I became closer with my siblings. Very close,” she chuckles.

When asked if she still thinks of the Dakota Crescent estate, she replies, “Last time, I will. But I thought that thinking about it is useless. You think of it but it’s not there anymore. Thinking doesn’t change anything. Occasionally, I’ll reminisce how life used to be over there.”

“Sometimes I’ll remember, or dream about what I was doing at Dakota.”

Researched & Written by Charmaine Poh

Photography / videography by Charmaine Poh, Jeremy Ho, Amirah Haris